NFL Afterlife: Joe Horn

Joe Horn’s path to the NFL was far from traditional. A twisty road took Horn from community college to a bevy of fast foods jobs to make ends meet before trying out for the CFL. Only a technicality with his CFL contract made the NFL a possibility.

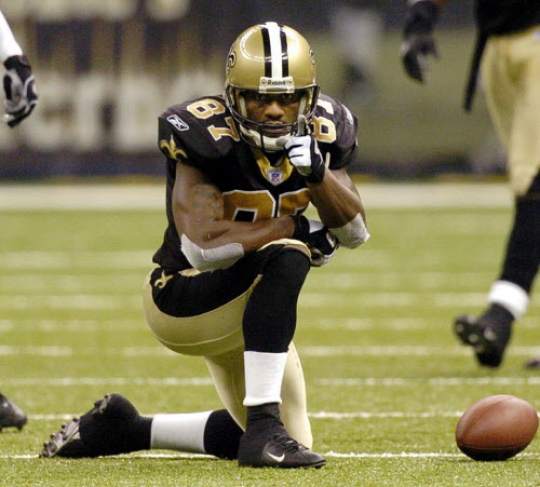

After being drafted in 1996 by the Kansas City Chiefs in the fifth round, Horn was mostly a special teamer before signing with the New Orleans Saints in 2000. He immediately catapulted onto the scene in New Orleans with 1,342 yards and 8 touchdowns that first year. Horn would earn four Pro Bowl berths as a Saint but was equally remembered for one of the most talked about end-zone celebrations of all-time: pulling out a cell phone he had hidden in the goal post.

Since retiring in 2007, Horn has morphed into a successful entrepreneur – selling a product near and dear to his heart…and stomach. He also recently obtained a provisional patent for an app that helps golfers locate their lost clubs.

In our Afterlife conversation, Horn dishes on his new career, what the city of New Orleans means to him, shares his strong feelings on Roger Goodell and much more.

MJ: Let’s talk sauce. Are you still selling your Bayou 87 sauce?

JH: I am still doing my barbeque sauce – which is my recipe – plus my smoked sausage and Cajun rub. I’m kind of under the radar because many players go into broadcasting when they retire. I took another road – the food industry. It’s going very well; in fact, I’m in with Sysco Foods and US Foods. Once you’re with them, it kind of shoots out on its own. It took awhile to establish this. Just like football where it took awhile to become a Pro Bowler.

MJ: Yes, I remember reading that at one point during your circuitous path to the NFL that you were bought a Jerry Rice workout video to help you stay in shape?

JH: I was in shape. I had like $2-$3 dollars left to my name. I was in a Blockbuster and saw Jerry’s video for $3.00 so I decided right then and there to invest in my future and learn from the best receiver in the history of the NFL. This is when I was also working at a Bojangles Chicken.

MJ: Why were you down to your last few dollars then?

JH: I was living with my mom then and in junior college and we just had no money. When I sent money back to my little girl in Mississippi that would leave me with just about nothing.

MJ: What did you learn from Jerry in that video?

JH: Basically how to work cone drills. I sharpened up my mind and skills and it helped me stay focused on my dream to play in the NFL. That tape wasn’t bought to help me stay in shape. It helped me mold my career and stay on my path. It helped my life. It kept me out of the streets.

MJ: So then you’re off to the CFL.

JH: I played one year in the CFL. That’s an interesting story. I played for the Memphis Mad Dogs and after that year all the teams in the States folded. Once you fold, if you’re in a two-year deal, your contract automatically goes into a draft and anyone can take you. I had 1300 yards that year and was almost Rookie of the Year so I was one of the hottest tickets. The Calgary Stampeders were getting ready to draft me. However, my agent called them on draft day and threatened to sue if they put my name in the draft because they sent my contract to another person’s address on the day it had to be signed and legally I wasn’t bound to the Memphis Mad Dogs anymore.

MJ: So that’s how you made it to the NFL when you did?

JH: Exactly. Most people have no idea that I probably never would have been in the NFL if my agent hadn’t threatened to sue.

MJ: You were drafted in the fifth round by the Chiefs. How were you discovered?

JH: No one knew much about me so I was a sleeper. But Chiefs offensive coach Jimmy Raye who was from Fayetteville, where I lived, worked me out. Jimmy went back to Marty Schottenheimer and said ‘We have a kid here who is one of the best receivers in this draft that no one knows about.’

MJ: Describe how you felt when you got the call that you had been drafted.

JH: I made a promise to myself that after all the suffering, living in the projects, that if I can touch the Kansas City grass I’m going to kiss the ground and become a household name.

MJ: Given your difficult financial upbringing, how did it feel to finally know you were going to be all right?

JH: It’s a funny feeling – I felt good for everybody else in my family. I feel like God chose me to make money. But I was also there to help anyone who needed it. If someone needed help in the grocery line, or military at a restaurant, my job was to take care of the bill.

MJ: Good for you.

JH: Just like when Hurricane Katrina came along – I don’t tell too many people what I did financially – but I felt like I owed the state of Louisiana. It was my obligation. If there was an employee who didn’t have a job, or they had to be displaced and they came across my path – or they knew someone who knew someone who knew me – they were going to get a check in the mail, their bills paid, a minivan for their kids. I was going to do whatever I had to do to take care of anyone I knew was suffering.

MJ: That’s really great. And obviously you felt a strong connection to New Orleans.

JH: Without a doubt.

MJ: When you got to New Orleans and became a national name in 2000 – your breakout season – how did that happen. Was it the system or did something change in your regiment or mentality?

JH: It was all that, but really the city. New Orleans will embrace you will but it’s all about how the athlete embraces New Orleans back.

The city of New Orleans embraces their athletes and most of the athletes that come there don’t understand the struggle, what people have gone through the last 20 years. Louisiana is so home grown that they will take anyone that will help a franchise and put them on a pedestal that no one can knock them down from. If you’re an athlete and you get off the plane cocky, treat it like a stop that you’ll be for a little while, they’ll chew you up and spit you out.

MJ: So that mindset was a prominent factor in your rise?

JH: The motivation was people didn’t like the Saints. When teams played the Saints they knew it was a win. The disrespect the other teams had for the Saints is what fueled me.

Here’s something you may not know. When NFL players go to the Pro Bowl, they do this thing where they exchange helmets. When I went to the Pro Bowl I didn’t give my helmet to anyone because I know they didn’t really want it and so I didn’t want them to have it. That’s how much New Orleans meant to me.

There was a guy, the third year I went to the Pro Bowl, the kicker David Akers and he said to me, ‘Joe, I know not many people ask for a Saints helmet but will you give me yours and I’ll give you mine?’ That was one of the most exciting times I had going to Hawaii because I hate flying.

MJ: But you made that trip, what, four times?

JH: Yeah, I made it four times but canceled twice because I hate to fly.

MJ: So you called up the league office and said ‘Sorry no Pro Bowl for me – I don’t want to fly?’

JH: Well, I didn’t really tell them that. I just made up an excuse.

MJ: What about all the flying you had to do in season?

JH: I took Ambien pills all the time. That’s why I like Madden. He didn’t fly. I had my bus take me around too. My driver would drive, for instance, to Nashville if we were playing the Titans and wait for our plane to get there. If we beat the Titans, my coach would let me take my bus back home.

MJ: So you had the Horn Cruiser?

JH: I still have it in Laurel, Mississippi and my driver, James Perkins just waits on me to call. I’m not going to get in it to go golf – it’s like $500 to fuel up. But If I go somewhere – like I’m going to Vegas this week because I’m now the spokesperson for Joyner Compression Socks – I’ll consider taking it.

MJ: Onto one of your other “products” – the cell phone. Did you actually call someone after you scored?

JH: I called my son, Jaycee. It was a Sunday Night game against the Giants but my kids had to go school Monday and of course I usually don’t get home until 12 or 1 in the morning. So they couldn’t go. And my son, who was like 6 at the time, was crying as I walked out the door. I said, ‘I’ll call you.’

That was a big year for end zone celebrations with T.O. and Chad and myself and I just decided that I was going to shut this end zone celebration stuff down.

Mike McCarthy, our offensive coordinator had me in on something like nine of the first fifteen plays. Aaron Brooks didn’t know anything about it. Jim Haslett didn’t know anything about it. No one knew I was going to do this except for Michael Lewis who put the phone in the end zone I told him to put it in.

MJ: Do you watch games regularly these days?

JH: Oh yeah. And I keep up on all the news.

MJ: What are your thoughts on the current state of the NFL?

JH: Can I be honest?

MJ: Of course.

JH: Here’s what I don’t like. I don’t like what Roger Goodell is doing. He has so much power that he can almost shut people down. I just don’t like him. And I don’t like that on draft day these kids don’t know that they’re hugging the devil. I hate to see kids that are lost and then happy but they really don’t know that the man they’re hugging will rip their throat apart. If he has an opportunity to take money from them, or there’s a situation where they’re guilty before they go to court, he’ll rip them apart. And there’s nothing no one can do about it. If the owners are happy with Roger Goodell, the fans, the media, no one can take his job from him. I hate it.

MJ: Is it mostly the fines? His commissionership has obviously been rooted in being an authoritarian.

JH: The owners gave him that power. He doesn’t work for the players.

MJ: Yeah, but the players gave him power to continue to operate under the clause that makes him judge and jury. It’s ridiculous that he’s the one hearing Tom Brady’s appeal but his right to do so is protected under the CBA.

JH: First of all, people need to understand he works for the owners and understands his power. People like Cris Carter and Chris Berman ,who can usually say what they want, they can’t say anything bad about Roger Goodell or he’ll cut their throats.

They’re going to kiss his ass, too. They know their job could be snatched away by his power. This man makes what, $14 million a year?

MJ: Actually, over $40 million a year.

JH: C’mon! And the whole Brady thing, I’m not mad at Tom. He’s a great athlete and he does what he needs to do to win the football game. If he deflated balls and the guys did for him, I’m not mad at Tom for that. Guys do things all the time to get ahead that the NFL doesn’t know about.

Who I’m mad at, who I do disrespect and who should be suspended for a year, it should be his head coach because he knows what everyone is doing.

MJ: Interesting. Well, in closing I just want to throw a few things out there and have you give me a one or two word response that comes to mind.

JH: Ok, sounds good.

MJ: Who’s the best WR in the game today?

JH: Can I give you two?

MJ: Of course

JH: Roddy White and Marques Colston

MJ: Toughest defensive player you faced?

JH: [Former Kansas City Chiefs cornerback] Dale Carter

MJ: Aside from your cell phone celebration, the second best TD celebration?

JH: When I scored on Terence Newman. There were “We Love the Troops” signs all over Cowboys Stadium because it was during Iraq. I pointed at the sign and walked over and hugged it.

MJ: One word or a few words to describe the current state of the NFL

JH: All about the money.

MJ: What will you be doing in 10 years?

JH: I’ll be a regular shark on Shark Tank.